The problem with medicine is that it remains dominated by imperialist Western interests and practices. Economic gain has been prioritized over the well-being of our population. Our countries remain dependent on the West for medical essentials, technology, resources, and decision-making. We are trapped in a vicious cycle of exploitation due to an unequal relationship. This dependence perpetuates an unequal global health discourse which continues to marginalize our experience and needs.

Medical imperialism is a system whereby the West and developed world use language and resources in medicine to maintain dominance over developing countries. It is well known that colonialists and capitalist imperialists extract resources from our country and continue to suck the life out of it. This is best seen in how France is holding onto its former African colonies with a white-knuckled grip. Multiple countries in West and Central Africa are chained to France through their continued use of the Franc of the Financial Community of Africa or CFA franc. Sure, the central banks of the respective countries determine the amount of currency to be printed…in France. Not to forget that the involved countries must also deposit half of their foreign exchange reserves with the French Treasury.

This is a great example of how Western imperialists continue to meddle in our countries. The continued use of the CFA franc cements the hold of neocolonialism on Africa and is a major threat to the sovereignty of the affected countries. Guinean citizens knew this when in 1958 a constitutional referendum was held in the, still, French colony. The new constitution would grant Guinea a chance to join the French Community, but its citizens voted a loud and resounding “NO” when results were announced. They had chosen independence and in doing so became the first French territory to seek independence. Well, the French accepted defeat and cordially withdrew from the nation, giving the Guineans the chance to finally exercise their freedom…not really. France retaliated with unrelenting spite to the vote. They withdrew all their civil servants from the budding nation, and suspended bank credits and all developmental assistance. The Washington Post reported that “as a warning to other French-speaking territories, the French pulled out of Guinea over a two-month period, taking everything they could with them. They unscrewed light bulbs, removed plans for sewage pipelines in Conakry, the capital, and even burned medicines rather than leave them for the Guineans.” Despite this, the currency was withdrawn in Guinea but is still in use in 14 countries across West and Central Africa.

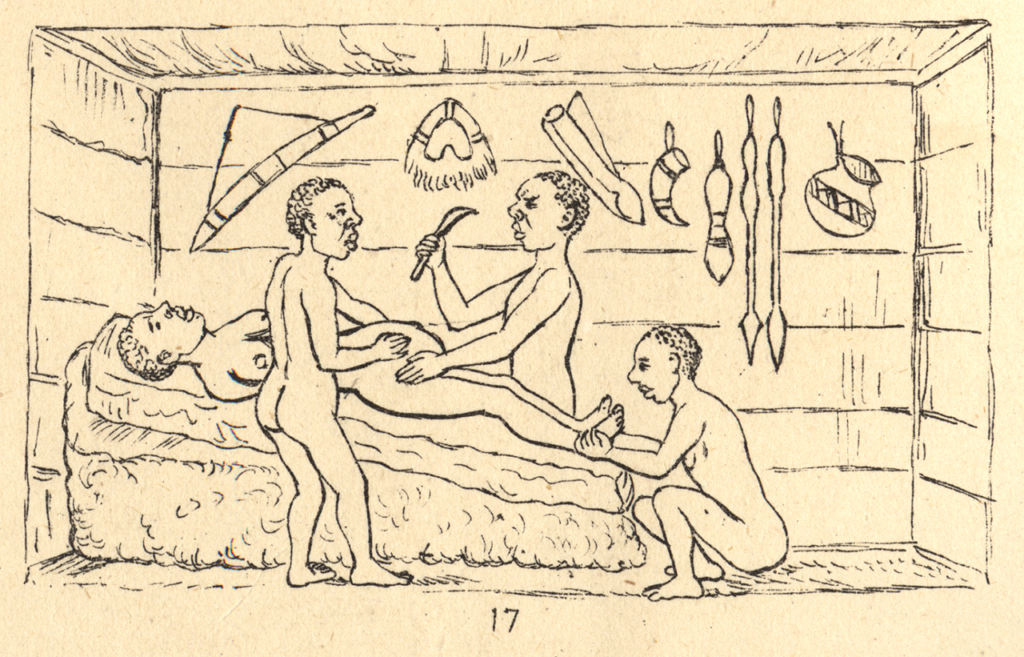

Colonialists used race theory to validate imperialism. Racist ideas are perpetuated through medical research, conferences, journals, institutions, and medical careers. A particularly heinous example was seen in the experimentation on enslaved black women by J. Marion Sims, the hailed ‘Father’ of modern gynaecology. Sims operated on enslaved black women without anesthesia which was in line with the popular racist belief that black people did not feel pain as white people did. Of course, the famous Tuskegee syphilis trials of 1932 –1972 is another pattern in the cloth of history that has embedded itself in the annals of medical ethics. Furthermore, indigenous medicine was rejected, and modern medicine was used to push the values of “civilization” and “assimilation”. Through centuries of European invasion, western medicine and culture settled into Africa leaving little space for traditional medicine to progress. Efforts by colonialists to marginalize and create a stigma around indigenous medicine destroyed the industry. They branded it as witchcraft and reinforced the belief that Africa was a continent shrouded in darkness and filled with superstitious, backward folk. We lost pride in our knowledge and discarded it for the ‘civilized’ system. This is even though evidence shows that Caesarean deliveries were being performed in the Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, and neurosurgical procedures such as trepanning were well established.

These legacies remain in our health system which is warped in consistent and structural ways. In the past there was segregation with white settlers being afforded healthcare in exclusive hospitals while the rest of the population was neglected and left to rely on ‘native hospitals’. How can you provide healthcare to a citizenry with fewer legal rights? In the present, this is reflected by the privatization of healthcare. The wealthy and political class have access to quality care in private facilities, while the impoverished majority are left with limited options. The burgeoning middle class is caught in the crosshairs as their private insurance affords them the lofty belief that they are immune from this disparity. They are not and the fragility of such a system cannot sustain a nation. Public hospitals that serve most of the population are underfunded, underequipped, and understaffed. Over-reliance on the private sector continues to weaken our public health system.

Healthcare has been made a commodity to be bought and sold instead of being a fundamental, essential service available to everyone. The West continues to profit from our diseases and medical needs, leaving us reliant on them for medical technology, vaccines, and infrastructure. This is clearly seen in how international pharmaceutical companies control drug development, pricing, and distribution. This control undermines equitable access to essential medicines and treatment in developing countries. Multinational pharmaceutical corporations hold patent monopolies and set high prices for essential medicines which makes treatment inaccessible for many Kenyans. The rising cost of healthcare has led to unfathomable medical debt and poverty, with many Kenyans choosing to forego essential medical care entirely. Weak regulatory frameworks for the pharmaceutical industry and medical research facilitate the exploitation of developing countries. Imperialism creates new markets for medical products from dominant nations, hindering local research and development. Despite all of these, free maternity services in public hospitals and free primary health care in primary care facilities have successfully been provided.

Donor-driven disease campaigns often favour vertical programs targeting specific disease e.g. HIV/AIDS rather than focusing on strengthening our public health infrastructure. This neglects the broader healthcare system and does not fill the gaps in care, creating a system that is unsustainable. An occurrence that exemplifies this unsustainable model is the workings of PEPFAR, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Last year in August the support offered by PEPFAR was jeopardized after Kenyan Members of Parliament sent a letter to numerous U.S lawmakers. The letter contained their disapproval of PEPFAR support of abortion services in the country and called for a stop to such services before its reauthorization. This led to mass disputes with the US threatening to not renew the funding which contributes more than 50 per cent of total HIV/AIDS care funds in Kenya. In a fell swoop, the future of the campaign against HIV/AIDS was uncertain. That is not sustainable.

Structures and policies that do not work for us also exist. The IMF and WHO provide loans with added conditions that burden our country. This hinders our ability to invest in public health. Structural adjustment programs (SAPs) also limit the policy space for our country to prioritize health. The WHO has also failed to prioritize equity and the rights of developing nations. Previously, it was focused on preventing epidemics for trade protection and advocating for universal healthcare. However, financial dependence on the World Bank has renewed its focus on vertical interventions and economic considerations in its health policies. Focusing on economic growth and stability over health equity leads to underfunding of public health systems and reliance on market-based solutions. Nonetheless, several acts have been passed to improve public health coverage. These include the Primary Health Care Act, Facility Improvement Financing Act, and Digital Health Act.

There is a barrier to accessing medical education with the introduction of the new university funding model that is already in practice. This new model has led to exorbitant university fees and is dashing many hopes for higher education. Even though there is an increase in the number of medical schools, more students are opting out of joining university. Eventually, only the well to do will be able to afford an education. This reduces diversity, meaning that medical professionals will come from higher-income families, and they tend to align themselves with capitalists’ class and resist any social change that threatens the current class structure. The ongoing mass recruitment of healthcare professionals from Africa to work in countries with higher salaries also leads to a shortage of skilled workers, further weakening the already fragile healthcare system.

It can all seem very bleak, the future dark and unpromising but there is a silver lining somewhere in this dismal state of affairs and that is our indomitable spirit. We saw it in the Guinean’s fight for economic independence and we are seeing it now all over the continent. The smell of change and revolution is in the air. Our forefathers fought against insurmountable odds and with their sweat and blood we are able to freely publish this article without fear of arrest or silencing. As such we cannot sit back and let other external forces dictate whether you can access essential healthcare. How do we go about that? Firstly by exercising our civic duty; be it on the street, public participation in legislative bills or voting in and holding accountable qualified leaders. The ongoing protests and renewed interest in our governance by our generation is building the scaffold for better changes.

Closer to home; to our fellow students keep studying! There is a dire need for more healthcare workers in health administration. Start entertaining ideas of pursuing an MBA post-graduate or a management course. Gone are the days when medics could afford to focus solely on the clinical aspects of health. And as you slog your way through your studies maintaining a firm, non-negotiable sense of morals is required. It all starts with you. Soon enough you will be a superintendent or a member of a hospital board. The task of curbing the miasma of corruption and mediocrity that is plaguing our country will fall into your capable hands one day.

In conclusion, what we need is to dismantle the structure of medical imperialism and build a healthcare system that truly serves the needs of all people regardless of their geographic location and socioeconomic status. This can be done by fighting corruption, increasing investment in local infrastructure and research, making fair intellectual property rights for essential medicines, and a stronger global health governance that prioritizes equity and the rights of developing nations. In light of the continuing protests concerning the governance of our country, we have proven to ourselves the importance of continued dialogue, thorough civic education, and holding policymakers accountable. We would love to hear your thoughts in the comments.