Overview

Neck trauma includes both blunt and penetrating trauma. The airway is a major concern in neck trauma. Patients who present with hypoxia, stridor, neck distortions, or hematoma should be intubated immediately. Blunt trauma is primarily managed based on symptoms and imaging (CT) results, whereas penetrating trauma is managed both on symptoms and zones of injury (anatomically focused). Penetrating trauma more often results in an injury that requires operative repair, whereas blunt trauma commonly results in cervical spine trauma.

- Causes of blunt neck trauma

- Sports-related

- Motor vehicle accident

- Strangulation

- Excessive chiropractic manipulation

- Causes of penetrating neck trauma

- Stabbing

- Gunshot wound

Vascular, aerodigestive, and neurological structures can be damaged in neck trauma

| Structure | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Larynx | Hoarseness, dysphonia, edema, pain below hyoid bone, crepitation over thyroid cartilage |

| Trachea | Tension pneumothorax, upper chest crepitation |

| Esophagus | Hematemesis, dysphagia, odynophagia, soft-tissue crepitus, saliva leaking from the wound, pneumomediastinum |

| Vascular | Expanding hematoma, weak/absent pulse, bruit, thrill, cerebrovascular accident (contralateral hemiparesis, loss of consciousness) |

| CN X | Voice abnormalities, vocal cord asymmetry |

| CN XI | SCM, Trapezius weakness |

| CN XII | Tongue deviation towards the affected side |

| Phrenic Nerve | Asymmetry of the diaphragm on CXR, use of accessory muscles of breathing |

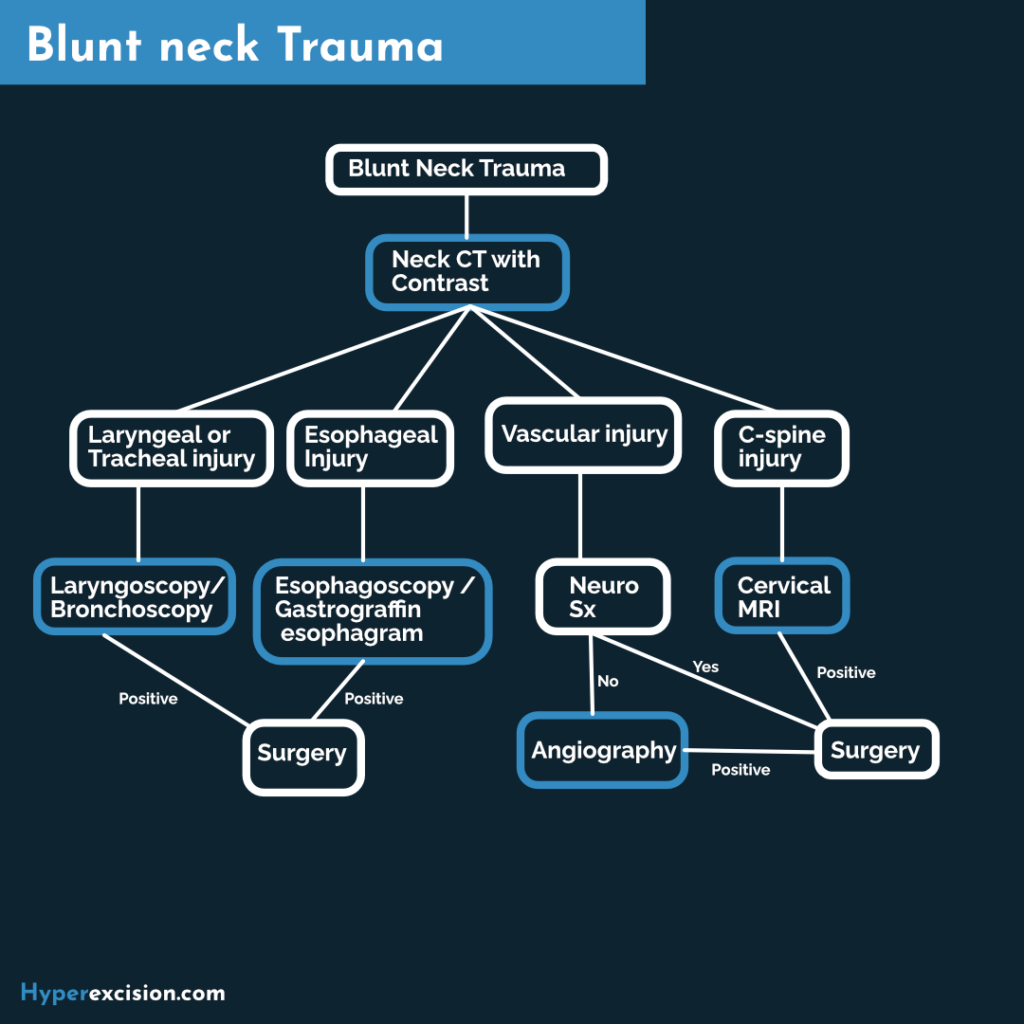

Blunt Neck Trauma

In blunt trauma, the area of injury may be larger and injuries may not be apparent. It presents a greater diagnostic challenge than penetrating neck trauma. The airway and cervical spine are at the highest risk of damage. All blunt trauma patients should be considered to have cervical trauma until proven otherwise. The esophagus has a lower risk of damage compared to penetrating neck trauma.

- Investigations

- Neck CT with contrast: best initial test provided the patient is stable and has no signs of impending airway compromise

- Vascular damage and symptomatic patients (especially neurological symptoms) → Operating room

- Other tests to investigate for problems based on CT findings

- Laryngeal injury → Laryngoscopy → ENT consult/Operating room

- Tracheal injury → Tracheoscopy → ENT consult/Operating room

- Esophageal injury → Esophagoscopy or Gastograffin esophagram → Operating room

- Vascular injury, no neurological signs → Angiography → Operating room

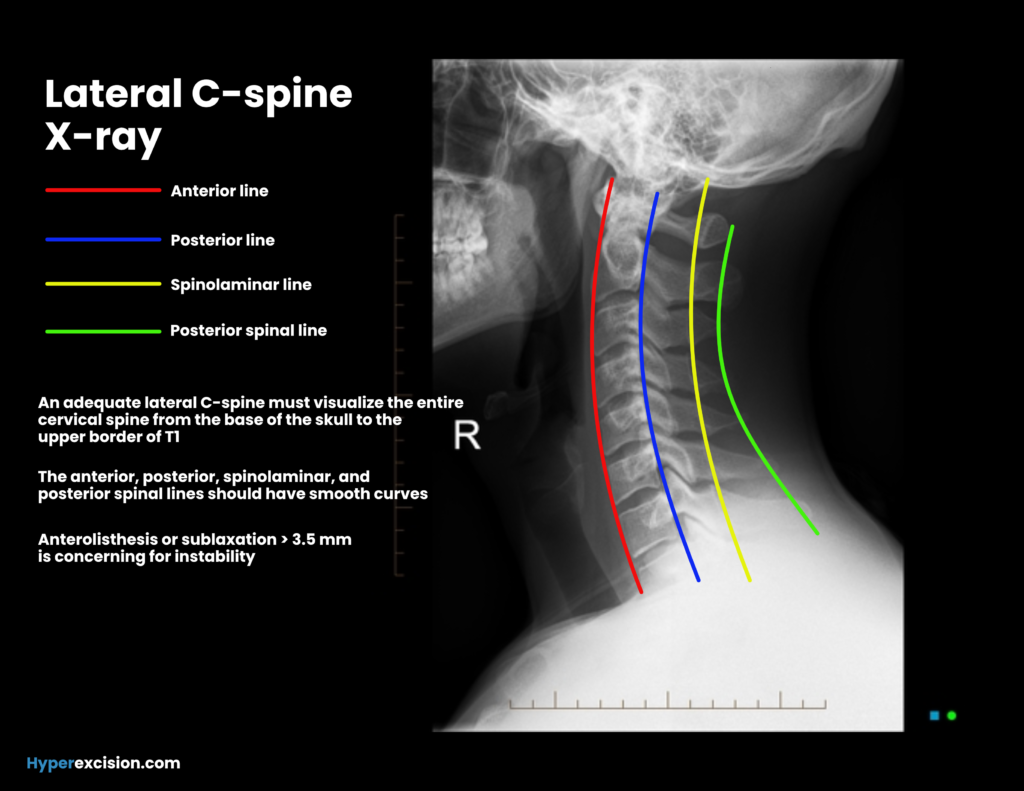

- C-spine injury → cervical MRI → neurosurgical consult

- Neck CT with contrast: best initial test provided the patient is stable and has no signs of impending airway compromise

- Non-surgical treatment options for C-spine injury

- Cervical orthosis: immobility with an Aspen or Philadelphia cervical collar.

- Halo vest: maintained for 3 months

- For patients unreliable to wear cervical orthosis or who need surgery but are poor operative candidates

- Cervical traction: with Gardner-wells tongs

- Maximum weight is 5kg per cervical spine level (C6 injury allows a maximum weight of 30kg)

- Indicated for subaxial C-spine fractures with malalignment, unilateral or bilateral facet dislocation, and C1-C2 rotatory subluxation

- Indications for surgical treatment of C-spine injury

- Angulation > 11 degrees

- Translation or displacement >3.5 mm

- Unstable injuries after cervical orthosis or Halo vest placement

- Surgical treatment options for C-spine Injury

- Open or closed reduction (if needed)

- Fusion of the involved spine segment

Clearing the C-spine

A clinically significant c-spine injury is any fracture, dislocation, ****or ligamentous instability detectable by diagnostic imaging and requiring surgical or specialist follow-up. Due to the low incidence of injury, neck CT on all patients with blunt trauma is expensive. Screening tools (NEXUS criteria and Canadian C-spine rule) have been developed to identify high-risk patients

Step 1: Make sure you have an alert and oriented patient

Step 2: Make sure they have no neck pain or neurological injuries

Step 3: Examine the neck

Step 4: Remove the C-spine collar and check for painless full active ROM and no pain to palpation of the spine

- NEXUS Criteria for clearing the C-spine

If all these criteria are met imaging is not required to exclude a clinically important CSI

- Alert and oriented

- No drugs or alcohol

- No head injury

- No neck pain

- No neuro symptoms

- No painful distracting injuries

- Neck exam for C-spine injury

- Swelling or edema

- Bruising

- Painless full active range of motion

- No pain to palpation of cervical spines

- Practical steps for clearing the C-spine

- Step 1: Make sure you have an alert and oriented patient

- Step 2: Make sure they have no neck pain or neurological injuries

- Step 3: Examine the neck

- Step 4: Remove the C-spine collar and check for painless full active ROM and no pain to palpation of the spine

Penetrating Neck Trauma

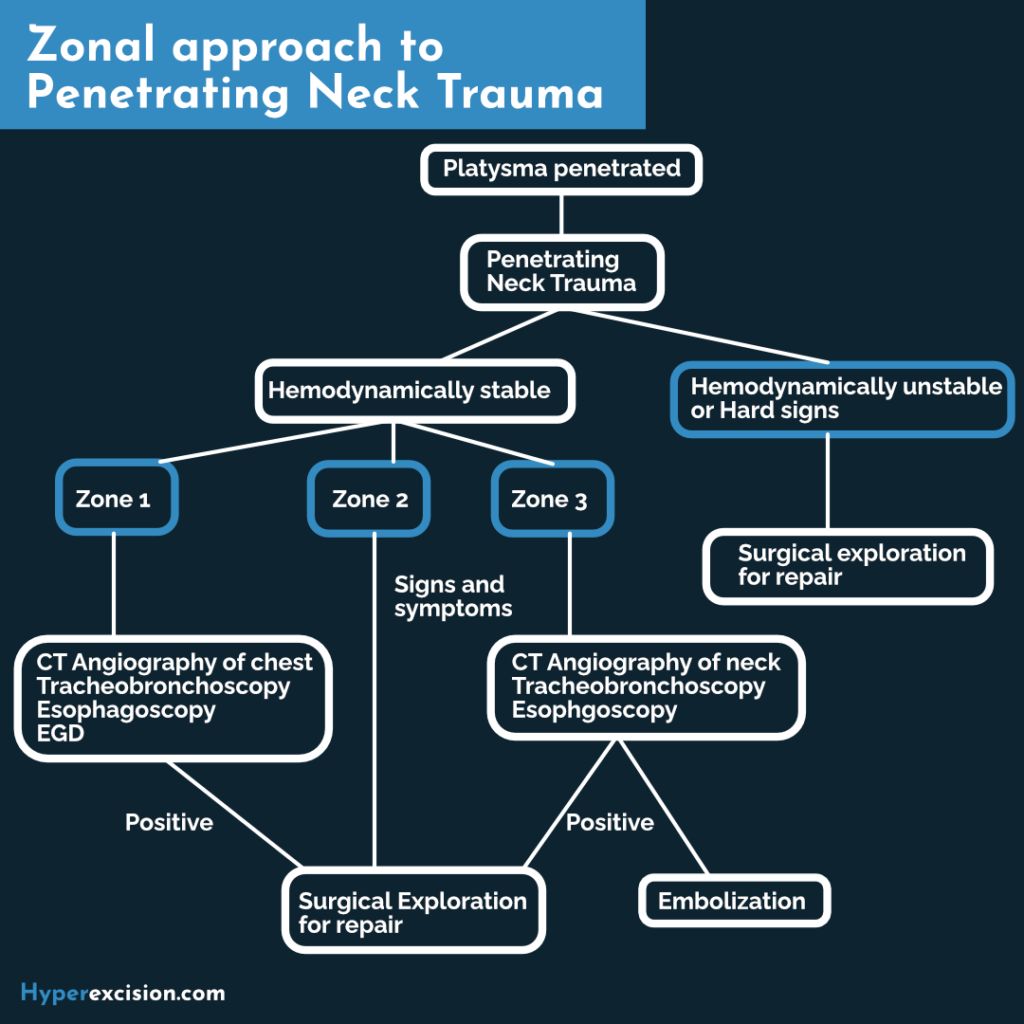

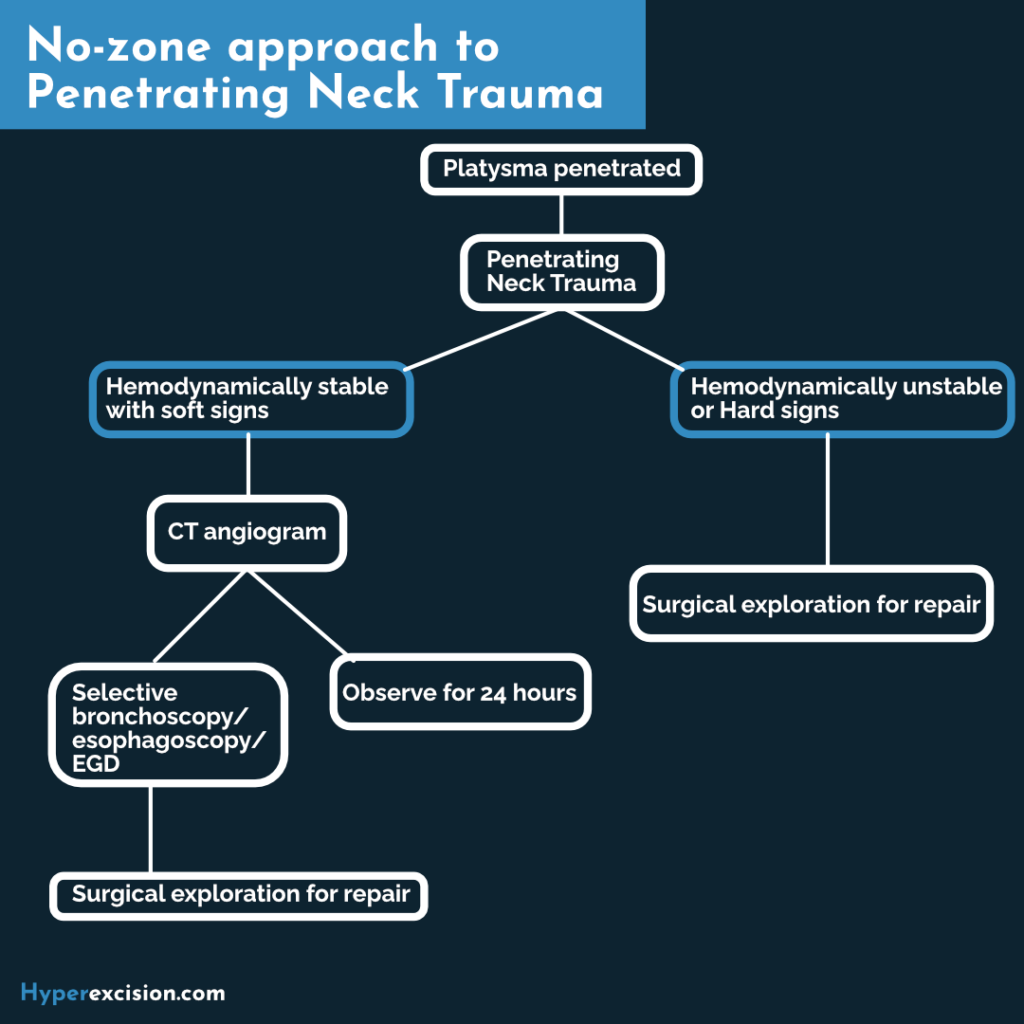

A penetrating neck injury is any injury where the platysma is violated. The neck is very vascular with important vessels traversing it. Vascular injuries can be life-threatening: hematoma formation (airway compromise), transection of the vessels (cerebrovascular accident), and exsanguination. If the patient is bleeding they should be resuscitated first if necessary. Impaled objects should not be removed until the patient is in the operating room. Management of penetrating neck trauma has evolved from a mandatory exploration approach into a selective exploration approach (exploration is recommended for Zone II, and Imaging and diagnostic tests for Zone I and Zone III). Where CT scans are readily available, some surgeons utilize an even more selective no-zone approach (imaging is done regardless of the zone of injury)

- Indications for immediate neck exploration (“Hard signs”)

- Vascular

- Shock (after resuscitation)

- Enlarging hematoma

- Active bleeding

- Carotid, brachial, or radial pulse deficit

- Aerodigestive

- Massive hemoptysis/hematemesis

- Air bubbling from the wound

- Massive Subcutaneous emphysema

- Neurologic

- Deficits like hemiplegia that indicate cerebral ischemia

- Vascular

- Other signs that raise the possibility of damage to the vascular, aerodigestive, or neurologic structures (”soft signs”)

- Venous bleeding

- non-expanding hematoma

- Bruit

- Minor hematemesis

- Dysphagia

- Odynophagia

- Minor subcutaneous emphysema

- Hoarsness

- Investigations

- Trauma labs (CBC, BMP, GXM, Alcohol level, Urine toxicology)

- CT angiography of the chest for zone I

- CT neck with contrast for zone III

- Follow-up investigations

- Esophagoscopy

- Gastrografin esophagram

- Tracheobronchoscopy

- Aortic arch angiography

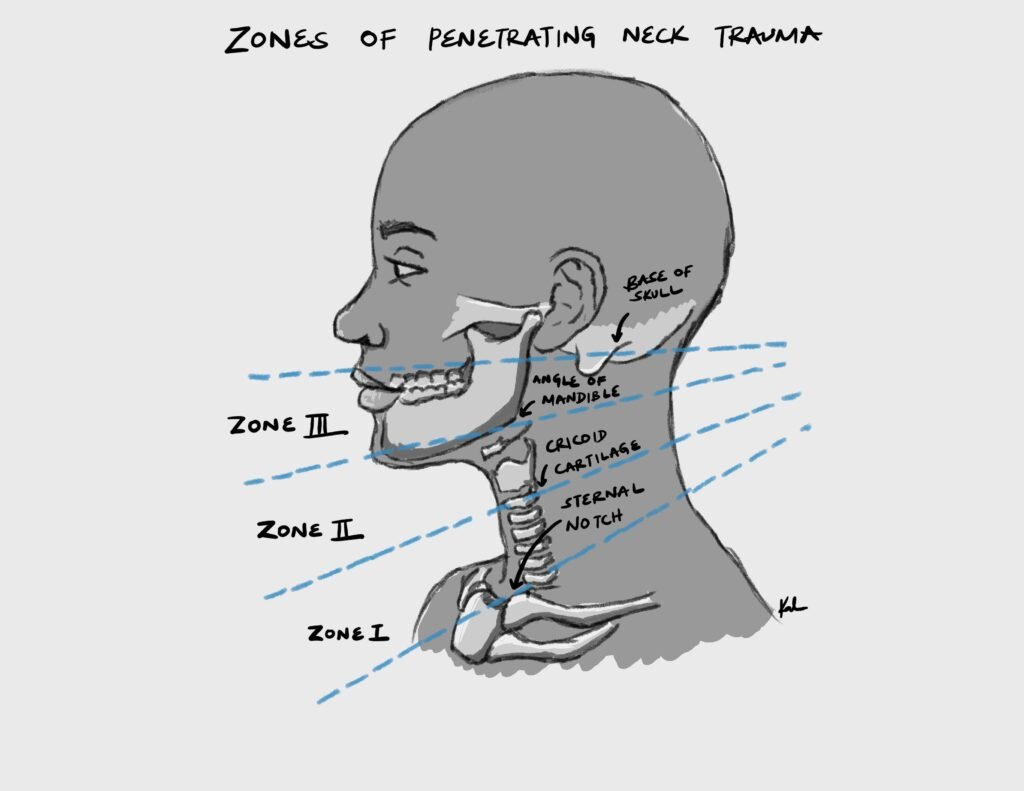

Zones of the neck

| Zone | Structures |

|---|---|

| Zone I | Aortic arch, proximal common carotid arteries, vertebral arteries, subclavian vessels, innominate vessels, lung apices, esophagus, trachea, brachial plexus, thoracic duct |

| Zone II | 80% of injuries. Common, internal, and external carotid arteries, internal and external jugular veins, larynx, hypopharynx, proximal esophagus |

| Zone III | Internal carotid artery, vertebral artery, external carotid artery, jugular veins, prevertebral venous plexus, and facial nerve trunk |