Overview

Patients do not die from an inability to intubate the trachea…they die from lack of oxygen

ASA defines a difficult airway as a clinical situation in which a conventionally trained anaesthesiologist experiences difficulty with facemask ventilation of the upper airway, difficulty with tracheal intubation, or both. It can be due to patient factors, clinical settings, or the skills of the anesthetist.

Physical Exam of the Airway

- Mouth

- Mouth opening: Note symmetry and extent, inter-incisor gap

- Dentition: Edentulous, loose teeth, teeth prominence. There is a danger of damage to prostheses and loose teeth

- Tongue size: Macroglossia increases the difficulty of intubation

- Mallampati class: Note whether the tonsillar pillars, uvula, soft palate, and hard palate are visible

- Jaw protrusion: assess forward protrusion of the lower incisors beyond the upper incisors

- Neck

- Length and thickness of the neck

- Neck movement (atlantooccipital joint extension): 35 degrees of extension is normal

- Evaluate for scars, masses, tracheostomy stoma, and tracheal deviation.

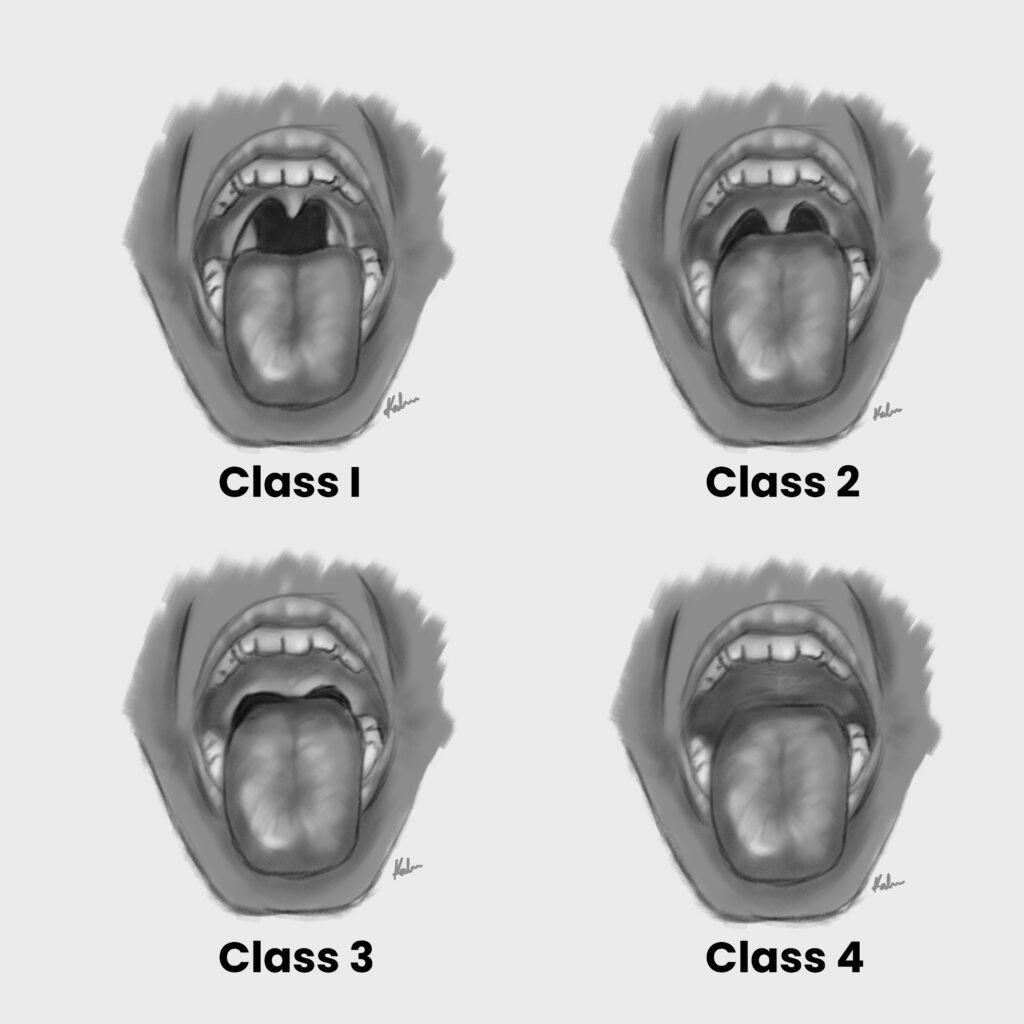

Mallampati Classification

The Mallampati classification is used to predict the ease of endotracheal intubation by visually assessing the distance from the tongue base to the roof of the mouth – and therefore the amount of space that is available to work with.

| Mallampati Class | View |

|---|---|

| Class I | Able to visualize the tonsillar pillars, fauces, uvula and soft palate |

| Class II | Only the fauces, uvula and soft palate are visible |

| Class III | Only the base of the uvula and soft palate are visible |

| Class IV | Only the hard palate is visible |

Cormack-Lehane Classfication

The Cormack-Lehane classification is used to grade the view of the larynx on direct laryngoscopy.

| Cormack-Lehane Grade | View |

|---|---|

| Grade I | Full view of the entire glottic opening |

| Grade II | Posterior portion of the glottic opening is visible |

| Grade III | Only the epiglottis is visible |

| Grade IV | No glottic structure is visible |

Pre-operative airway examination and non-reassuring findings

| Airway examination component | Non-reassuring finding |

|---|---|

| Length of upper incisors | Relatively long |

| Relationship of maxillary and mandibular incisors during normal jaw closure | Prominent “overbite” |

| Relationship of maxillary and mandibular incisors during voluntary protrusion of the mandible | Mandibular incisors cannot be brought anterior to maxillary incisors |

| Interincisor distance | Less than 3cm |

| Visibility of uvula | Not visible when the tongue is protruded in a sitting position (Mallampati >2) |

| Shape of palate | Highly arched or very narrow |

| Compliance of mandibular space | Stiff, indurated, occupied by mass, or non-resilient |

| Thyromental distance | Less than three ordinary finger-breadths |

| Length of neck | Short |

| Thickness of neck | Thick |

| Range of motion of head and neck | The patient cannot touch the tip of the chin to chest or cannot extend neck |

Conditions Associated with Difficult Intubation

| Condition | Reason |

|---|---|

| Arthritis | Decreased range of neck mobility. Increased risk of atlanto-axial subluxation in Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| Tumours | May obstruct the airway by compressing the trachea or by causing deviation |

| Oral infections | May obstruct the airway |

| Trauma | Associated with C-spine injury, base of skull fractures and facial bone fractures |

| Down syndrome | Associated with atlanto-axial instability and macroglossia. May also have a narrowed cricoid cartilage, and increased risk of post-extubation croup and subluxation of the atlanto-axial joint |

| Scleroderma | Decreased range of motion of the temporomandibular joint and narrow oral aperture due to thickened, tight skin around the mouth |

| Obesity | Increased risk of upper airway obstruction. Reduced mandibular and cervical mobility due to increased soft tissue around the head. Increased incidence of sleep apnoea. |

| Pregnancy | Increased risk of bleeding due to oedematous airway, increased risk of aspiration due to decreased lower gastroesophageal sphincter tone, increased incidence of sleep apnoea |

| Acromegaly | Enlarged tongue, epiglottis and vocal cords |

| Dwarfism | Associated with atlantoaxial instability |

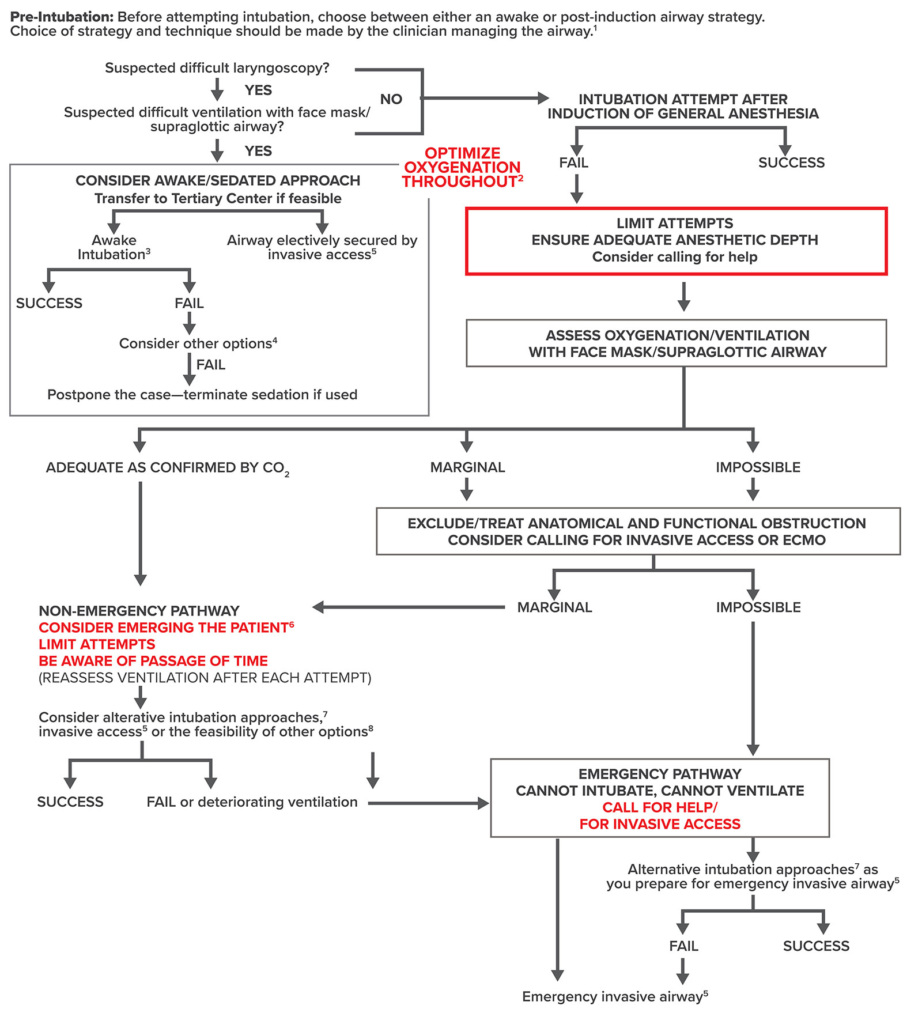

Difficult Airway

- Practical considerations with a difficult airway

- Awake or asleep intubation?

- Spontaneous vs positive pressure ventilation?

- Consider videolaryngoscopy (VL) as initial approach to intubation

- Pursue attempts at oxygen delivery throughout

- Call for help after the INITIAL unsuccessful intubation

- Place Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) immediately after unsuccessful intubation AND mask ventilation

- Do not postpone a life-saving surgical airway

- What options can be used to oxygenate the patient with a difficult airway?

- Mask ventilation in a sniffing position

- Oropharyngeal airway or nasal trumpet

- Laryngeal Mask Airway

- Nasal cannula: Including high-flow (Optiflow, ‘THRIVE’) apneic oxygenation

- Endoscopic mask e.g. Patil-Syracuse, to allow PPV with a face mask while using a bronchoscope

- Rigid bronchoscope side port for oxygen delivery

- Jet ventilation